Points that will be covered in a thorough class discussion are set out in the Suggested Response section. The questions on the comprehension test are identical in most cases to the discussion questions. Not all discussion questions are included in the test. The Suggested Responses are examples of excellent answers to the appropriate test questions.

1. Segregation can be defined as the separation of black and white Americans in social, political and economic spheres of life.

Describe:

(a) the ways in which blacks were harmed by segregation,

(b) the ways in which segregation harmed whites, and

(c) the way in which the failure to give equal rights to black Americans harmed the nation.

Suggested Response:

(a) Segregation, particularly in education and employment, denied black Americans the opportunity to realize their full potential, to be paid as they deserved for their work, and to live the American Dream. Segregation sent a message to blacks that they were inferior to other Americans; it was a mark of inferiority that was devastating to the self-esteem of many. It was a constant and irritating reminder that blacks were considered second-class citizens by their white compatriots.

(b) As to whites, segregation betrayed the political and cultural ideals of the Declaration of Independence. Relegating people to second-class citizenship because of their race undercut basic ethical lessons taught at home and in the churches and temples that whites attended. It is harmful to live in a way that takes unfair advantage of others. This harm may be more subtle than the harm from segregation suffered by a black person but it is nonetheless real.

(c) For the United States as a community, segregation betrayed the principles of the Declaration of Independence. By denying African Americans an equal opportunity to better themselves and contribute to society, segregation the denied country the full benefits of their talent.

2. What characteristics of population and tradition made Nashville a good place in which to mount a challenge to the segregation of department store lunch counters?

Suggested Response:

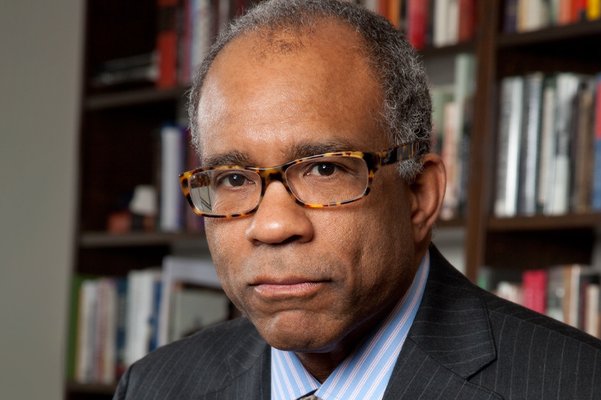

Nashville was generally thought to be an enlightened community with several colleges, black and white. Blacks had already been elected to the City Council and the School Board. There was a strong professional and middle-class component to the black community in Nashville. It was called the “Athens of the South” for its colleges and its reputation as being an enlightened community. There were many students from the black colleges to serve as volunteers. James Lawson, an expert in Gandhian nonviolence, was in Nashville and available to aid the students.

3. Explain the symbolic value of the lunch counters of downtown department stores targeted by the sit-in demonstrators.

Suggested Response:

Lunch counters were central and easy for the media to cover. It was particularly unjust for the department stores to sell merchandise to black people but not to allow them to eat at a lunch counter located in the store. The segregated lunch counters were a symbol that access to a place to eat, a basic human need, was being denied to the black community. The prospect of blacks eating next to whites would infuriate racists but also stress the humanity of the demonstrators and of all black people.

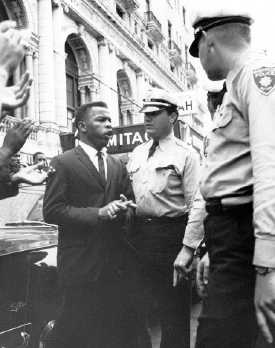

4. What happened on February 27, 1960, the day the students labeled “Big Saturday”? Did it work to the advantage of the students or that of the segregationists? Explain the reasons for your answer.

Suggested Response:

Agitators attacked sit-in demonstrators on February 27, 1960. Then the police arrested 81 demonstrators for disturbing the peace despite the fact that they had done nothing illegal and had been passive during the entire incident. No agitators were arrested. James Lawson, a leader of the demonstrations, named February 27, 1960, as “Big Saturday.” It led to outrage nationwide and helped the protesters prevail.

5. What would have probably happened had the demonstrators fought back when they were attacked?

Suggested Response:

Fighting back would have sacrificed the students’ moral authority as nonviolent protesters. It would have made the goal of mobilizing public opinion for desegregation more difficult by changing the focus of the controversy. The story in the press would be about the fight, rather than about the protesters’ complaints, their demands for change, and the viciousness of the segregationists. In addition, fighting back would have given the segregationists an excuse to hurt the demonstrators and would have given the police a justification for arresting them.

6. What strategic advantage did the demonstrators gain by deciding to remain in jail rather than posting the $50 bail?

Suggested Response:

Their purpose was to clog the court system and the jails, thereby increasing the pressure on the government.

7. Mr. Lawson instructed the demonstrators to look their attackers in the eye. What was his purpose in giving this instruction?

Suggested Response:

It brought home to the attackers that they were hurting human beings.

8. The sit-ins, the marches, and the boycott were designed to address many audiences. Describe some of the audiences and explain the demonstrators’ reasons for targeting them.

Suggested Response:

Seven of the audiences and the reasons for targeting them were: (1) the segregationists, because nonviolent mass action always seeks to change the minds of the opponents; (2) the public officials of Nashville, because they held the power of arrest and controlled the government; (3) the Nashville business community, because these people had a lot of influence with the public officials; this group was particularly vulnerable to the sit-ins because the controversy disrupted business; (4) the people of Nashville, because nonviolent mass action always appeals to the sense of justice of the community which can pressure those in power to change the policy, especially in a democracy; (5) the citizens of the nation, for the same reasons as the people of Nashville; the sit-ins were a major factor in getting Congress to pass a public accommodations law that prohibited racial segregation in restaurants, including lunch counters; (6) politicians outside of Memphis, particularly at the national level, for the purpose of convincing them to pass laws banning discrimination; and (7) the people of the world, because Americans and U.S. public officials would be embarrassed by the failure of the U.S. to live up to the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

9. The students considered the mass arrests to be a victory. What was their reasoning?

Suggested Response:

It meant that the government officials didn’t know how to deal with the protests. Arrests and imprisonment of many clean-cut, well-dressed college students angered the larger community and demonstrated that something was going on in Nashville that people should pay attention to.

10. When he was a young man, Mr. Lawson went to jail rather than cooperate in any way with the United States military. People have very different opinions about whether this was a patriotic act. However, looking at the accomplishments of Mr. Lawson over his long career, do you think he was a patriotic American?

Suggested Response:

This is an opinion question for which there is no single correct answer. A good answer will mention most of the following facts: Mr. Lawson knew what he thought was right and what he believed was best for the country; he acted on those beliefs. Even when he went to jail for resisting the draft, he didn’t try to run away and he didn’t try to take the easy way out. He stood up for his principles and took the punishment that society required of him. It is clear that he always had the best interests of the country at heart. Standing up for your principles is a very patriotic thing to do. Mr. Lawson’s work in the Civil Rights Movement was definitely a benefit to the country.

Questions 4 & 6 have been adapted from Question #3 in the Discussion Questions suggested in the website from the filmmakers. The answers have been supplied by TWM.