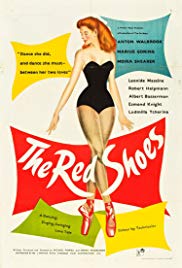

THE RED SHOES

SUBJECTS — Dance; Music/Classical;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Talent; Work/Career;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness; Citizenship.

AGE: 12+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1948; 136 minutes; Color. Available from Amazon.com.

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

SUBJECTS — Dance; Music/Classical;

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING — Talent; Work/Career;

MORAL-ETHICAL EMPHASIS — Trustworthiness; Citizenship.

AGE: 12+; No MPAA Rating;

Drama; 1948; 136 minutes; Color. Available from Amazon.com.

TWM offers the following worksheets to keep students’ minds on the movie and direct them to the lessons that can be learned from the film.

Film Study Worksheet for Social Studies Classes for a Work of Historical Fiction and

Worksheet for Cinematic and Theatrical Elements and Their Effects.

Teachers can modify the movie worksheets to fit the needs of each class. See also TWM’s Historical Fiction in Film Cross-Curricular Homework Project.

A young dancer is made a star by the world’s foremost dance impresario, but she must choose between her art and the man she loves. The film builds on the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale of the same name.

Selected Awards:

1948 Academy Awards: Best Art Direction/Set Decoration (Color), Best Musical Score; 1949 Golden Globe Awards: Best Musical Score; 1948 National Board of Review Awards: Ten Best Films of the Year; 1948 Academy Award Nominations: Best Picture, Best Film Editing, Best Writing of a Motion Picture Story.

Featured Actors:

Anton Walbrook, Moira Shearer, Marius Goring, Leonide Massine, Robert Helpmann, Albert Basserman, Ludmila Tcherina, Esmond Knight, Emeric Pressburger.

Director:

Michael Powell.

“The Red Shoes” describes the process by which ballet is made, highlighting the need for creativity and collaboration among a group of artists. The movie also shows: (1) the glamorous but insular world of a prima ballerina in the first half of the twentieth century; (2) the role of the impresario in the creation of a new ballet and the operation of a ballet company; and (3) the melding of different art forms (music, dance and set design) required for a world-class ballet company. In conjunction with The Turning Point (1977) and Dancemaker (1998), “The Red Shoes” illustrates the progressively more stringent technical/athletic standards required of dancers during the twentieth century (See Helpful Background Section).

MINOR. Absent from this film is an acknowledgment of the hour upon hour of grueling work in technique classes required of a ballet dancer. (This is more clearly seen in The Turning Point and Dancemaker.) The plot of “The Red Shoes” is based on the assumption that a woman must choose between a dance career and a fulfilling personal life. As modern prima ballerinas have demonstrated, this is no longer true. Like professional athletes, ballet dancers peak physically in their twenties. Many end their stage careers before the age of forty, leaving them in step with non-dancing contemporaries who have delayed childbearing for their careers. Some ballerinas have been able to have children during their careers.

Before watching the film briefly review with your child the history of the Ballet Russe and the remarkable character of Sergei Diaghilev. See the Helpful Background section. Immediately after the movie ask and help your child to answer the Quick Discussion Question. If your child is interested in dance you might want to watch the documentary “Ballet Russe” and the many other films listed in the Subject Matter Index under the heading Dance.

Ballet is a dance form in which lyrical beauty is attained through athletic prowess and rigorous training. It originated in France and Italy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, by the beginning of the twentieth century, ballet had ceased to be a serious art form in Western Europe. (There was an offshoot that survived in Denmark but Danish ballet did not have a major impact on the rest of Europe.) Beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century, Russia took the best of ballet from Western Europe. It imported performers and choreographers, learned from them, and made the art form its own. For example, Marius Petipa, the father of modern choreography, was a Frenchman who trained in France but worked in Russia for most of his professional life. Petipa was the ballet master for St. Petersburg’s Maryinski Theater from 1862 until his retirement in 1903. Petipa, while in Russia, choreographed forty-six original ballets, including many classics: Sleeping Beauty; The Nutcracker; and Swan Lake. Petipa revived and created entire new scenes for many existing ballets, including Giselle and Le Corsair.

Dancers from France and Italy performed in Moscow and St. Petersburg to enthusiastic crowds. By the turn of the twentieth century, Russian dancers and choreographers were making great contributions to the art form. The Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg provided the most rigorous ballet training in the world. Russian set design and costuming were rich, colorful, and far better than anything imagined in Western Europe. Ballet was supported by the Imperial government in Russia through large subsidies each year and was immensely popular. Seats to ballet performances were at a premium. They were purchased by organizations and handed down from father to son as a family legacy.

In Western Europe, during the same period, dance was confined to a supporting role for operas and musicals.

The character of Lermontov in “The Red Shoes” is based on Sergei Diaghilev (1872 – 1929). Western Europe rediscovered ballet in 1909 when Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes opened in Paris. The Ballet Russes was the first modern ballet company and, under Diaghilev’s direction, performed each year until 1929. The great balletic traditions of the West can be traced directly from Russia through Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. Marie Rambert and Ninette de Valois, both former Ballet Russes dancers formed separate companies. Valois’ company would become the British Royal Ballet. Rambert’s company started as the Ballet Club on a small stage at the Mercury Theatre referred to as a “postage stamp”. Viewers of “The Red Shoes” can actually see and hear this small stage in the scene in which Vicki is dancing in England.

You see and hear a crude gramophone, a swan queen ballerina about as big as the lake in the background, an a corps de ballet of swans you can count on the fingers of one hand. You also catch a grace-note glimpse of Rambert nervously watching from “out front” in the audience for things that can, and do, go awry. Ballet 101 pp. 75 & 76.

The Ballet Rambert still exists, now called the Rambert Dance Company focusing on modern dance.

George Balanchine (1904 – 1983), director of the New York City Ballet from 1948 to 1983, came directly from the Russian tradition, training at the Imperial Ballet School and later working as a choreographer for Diaghilev. Balanchine was the dominant influence on ballet in the United States in the second half of the twentieth century.

The Russian tradition of ballet continued to transfer talent to the West during the mid-twentieth century as dancers such as Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolph Nureyev, and Natalia Makarova defected from the Soviet Union. This infusion of well trained talented dancers, as well as Balanchine’s insistence upon technical proficiency, progressively elevated standards of performance in the United States after 1950.

During the last half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, Russia experienced a blossoming of all the arts, including music, visual arts, ballet, literature, and poetry. Diaghilev, due to the influence of his stepmother, was exposed to the arts as a child. He tried his hand at composing music without success. Then, through his personal magnetism and drive, Diaghilev organized art exhibitions in St. Petersburg. He edited and published Russia’s first magazine of artistic criticism, called “The World of Art.” When the Tsar withdrew his subsidy for the magazine in the wake of the financial constraints of the 1904 Russo-Japanese war, the magazine ceased publication and Diaghilev eventually turned to production of ballet, successfully integrating the disciplines of music, visual arts and dance. Diaghilev was frustrated by conservatives in Russia and by the death of his most important patron, the uncle to the Tsar. He then went to Paris and mounted art exhibitions there.

May 19, 1909 was the opening of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in Paris. Diaghilev brought to France some of the best of the Russian ballet, including Pavlova, Nijinsky and the choreographer Fokine. The Ballet Russes took Paris by storm and was nothing less than a massive artistic and cultural infusion from Russia to Western Europe. From 1909 until Diaghilev’s death in 1929, the Ballet Russes performed each season. Diaghilev was in charge of every production and coordinated all of the different artistic efforts that go into the creation of a ballet: the music, the set design, the costume design, the choreography and the dance. Diaghilev collaborated with some of the most talented Russian artists of his day, including the dancers Nijinsky and Pavlova, the composers Stravinsky, Mussorgsky, Borodin, and Glinka and the visual artists Benois and Bakst.

Diaghilev did not return to Russia after the Communists took power. While most of his productions were brilliant successes, Diaghilev never made money from the Ballet Russes. He required only a suite in a first class hotel and an occasional vacation. His clothing was often frayed and worn. When he died, the Ballet Russes was disbanded and its assets sold to pay its creditors. For more on Diaghilev, see The Influential Impresario. For more on the history of ballet in the West, see the documentary film “Ballet Russe”.

The instruments used in the modern orchestra include: the strings (violins, violas, cellos, base), the woodwinds (flute, clarinet), the brass (trumpets, trombones, French horns, tubas) and the percussion instruments (drums). The modern orchestra was developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with new instruments being occasionally added. Modern full scale orchestras have about 100 members.

The notes of the diatonic scale are described as flats, neutrals and sharps. The flat is one halftone lower than neutral. The sharp is one halftone higher than neutral. Not all notes have flats or sharps.

Hans Christian Anderson (1805 – 1875) was a Danish writer whose lasting contribution was 168 fairy tales, including: “The Ugly Duckling,” “The Emperor’s Clothes” and “The Red Shoes. ” Anderson’s fairy tales are simple, slyly humorous and often carry a moral message for all ages.

Monte Carlo is a leading resort city on the Mediterranean Sea. It has a famous gambling casino and is part of the principality of Monaco. Monaco consists of about 370 acres and has a population of 30,000. It is self-governing on many local matters. It uses the French Franc as its currency. Its foreign affairs are governed by France.

1. See Discussion Questions for Use With any Film that is a Work of Fiction.

2. Lermontov referred to ballet as his religion. What did he mean by that?

3. When Page and Lermontov were discussing whether she should come back and perform for the company and she told him that she was not performing very much, he immediately asked her if she had been attending class. She responded that she was attending class every day. What was the importance of this answer?

4. Read the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale entitled “The Red Shoes.” What is the relationship between the fairy tale and the story in the film? How are they different and how are they similar?

1. At the beginning of the movie, why did Craster and his fellow music students leave the theater in the middle of the performance of “Heart of Fire?”

2. Why did Lermontov object to his ballerinas being married or having strong love interests? In the movie the character tells us. What did he say? Was he right to do this?

3. Why couldn’t Page and Craster pursue their careers independently and still love each other?

Discussion Questions Relating to Ethical Issues will facilitate the use of this film to teach ethical principles and critical viewing. Additional questions are set out below.

(Be honest; Don’t deceive, cheat or steal; Be reliable — do what you say you’ll do; Have the courage to do the right thing; Build a good reputation; Be loyal — stand by your family, friends, and country)

1. What did Lermontov mean when he said to Craster that: “It is much more disheartening to have to steal than to be stolen from”?

(Do your share to make your school and community better; Cooperate; Stay informed; vote; Be a good neighbor; Obey laws and rules; Respect authority; Protect the environment)

2. How did Diaghilev contribute to Western Civilization?

The fairy tale, “The Red Shoes,” by Hans Christian Anderson.

In addition to websites which may be linked in the Guide and selected film reviews listed on the Movie Review Query Engine, the following resources were consulted in the preparation of this Learning Guide:

This Learning Guide was last updated on December 17, 2009.